In a world dominated by global capitalism, even our sexualities are up for sale

Corporate Paedophilia

Getting Real about Sexualization

What’s the evidence about young people’s sexual behaviour?

Nine out of ten parents feel that their views on sexualisation are misrepresented. Probably

The sexualisation of girls: beyond the moral panic

Are we seeing the sexualization of children or the infantilization of adults?

It’s good to talk: Liberal parenting and the sexualization of children

Sexuality education is stuck in a rut, and these ongoing sexualization debates are in part to blame.

We need a wider analysis of inequality, not the surveillance of young people

Queering the perspective: A call to recognize LGBT Youth in the sexualization of children debate

Nurturing Autonomy

Sex Shops: from the back streets to the high streets

Pornography: A filthy fruit

Life before Internetporn: the golden years?

Making sense of the sexualization debates

Sex-Positivity and Sexualization

Trigger Warning: Innocence Lost or Agency Denied?

pants-to-pants

It’s the autonomy, stoopid!

UK Consultation into Sexualisation of Young People. How useful are the findings?

Blog Post

In a world dominated by global capitalism, even our sexualities are up for sale

Sex has been commodified. The idea of sexuality being something we can work out and learn ourselves, the idea that it can be straightforward, simple and instinctive, has been replaced by an industry that sets up mystique and misinformation, then sells solutions. Let’s talk about the mechanics at work here.

The process of commodification works by identifying discrete categories of people (or defining new ones through the media), then creating categories of goods to match, assigning these goods prices, stimulating demand and then fulfilling that new, self-made demand. Markets quickly become saturated and prices drop: new markets are always needed, so new areas of demand are constantly being created. People are categorized into increasingly specialized areas, which offers businesses an advantage because their ‘needs’ can be more specifically and aggressively targeted.

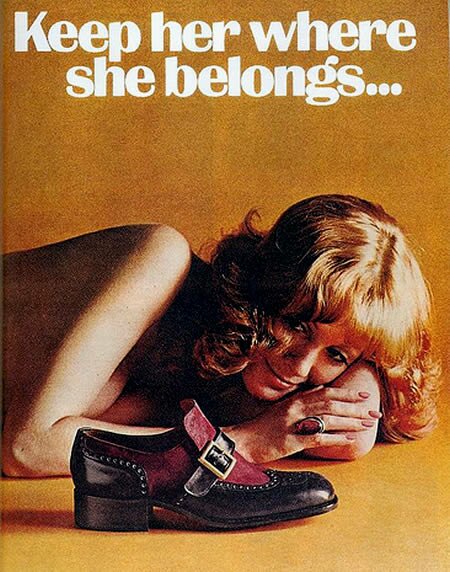

A classic example of this process at work is what author Naomi Wolf has called ‘the beauty myth’. The beauty industry creates and maintains its own ideals: the current concepts of beauty, as defined by the industry, did not exist until there became ways to spend money on them. Today, hundreds of companies target goods to a myriad of different consumer needs, many arising directly from mainstream beauty ideals: Lynx sell men deodorant by offering sexually available women, and Fair and Lovely offer employment and romance to Indian women who use their skin-lightening creams. Cynically, even the backlash has been commodified: Dove criticise the mainstream and successfully use their ‘Campaign For Real Beauty’ to sell soap. All these brands are owned by the same company: Unilever.

More recently, a relationship industry has appeared around what I’ll call the Mars-Venus myth. Gender differences are exaggerated in the media to reinforce the popular belief that communication between genders is impossible without guidance. External insight and expertise are marketed as essential for heterosexual fulfilment and partnership. In practice, much of this involves teaching heterosexual women to sell themselves to men. It’s also interesting to note the heavy use of economic terms in the dating scene: people speak of ‘being in the market’, of ‘getting’ a partner, ‘keeping’ them and ‘upgrading’ if they can. A glance at a magazine shelf will show a dozen different ways to market these myths. Nuts, Cosmopolitan, Men’s Health and Good Housekeeping all sell heterosexual fulfilment in various ways to people of different ages and social classes.

Nowadays, there are popular media claims that young people are inappropriately sexualized, overly affected by the clamour of consumerism and unable to make independent, informed sexual choices. It’s important to remember that this is the same media that propagates the above myths – newspapers must be sold, too.

Personally, I’ve collaborated with many young people in the anti-cuts movement. Despite media alarmism, my experience is that many young people are questioning these aggressively marketed myths and are educating themselves and their peers in more balanced, straightforward views of sexuality as part of their attack on capitalism as a whole.

The kids are fine: they’re well-informed, sensible and socially conscious. They’re increasingly open to alternative ideas and actively work to expand their worldviews. In the anti-cuts movement in particular, I’ve seen conversations spanning different classes and backgrounds, and many young people simply seem too busy making history to concern themselves with appearance or consuming prepackaged romance. In these spaces, capitalism seems to be losing its grip.

I’ve wondered before whether adults can protect young people from the harmful effects of sexualization while we ourselves are entangled in the beauty myth and besieged by the relationship industry. It may be that we instead have a great deal to learn from the ways in which young people are already questioning and challenging their world.

Ludi Valentine is an anti-cuts activist and aspiring sexuality educator. She’ll soon be informally blogging about sex toys, the commodification of sexuality and other geekery at .

Corporate Paedophilia?

Australia very recently had a debate about the sexualization of children. It was based on a report called ‘Corporate Paedophilia’ which was sparked by – of all things – a store catalogue.

In 2008, somebody picked up a catalogue. It was an ordinary catalogue from a fairly fancy store. Inside, there were pictures of women looking brooding and stylish in their fancy new clothes. There were pictures of men looking debonair and mysterious in their fancy new clothes. And there were pictures of children looking happy – wearing fancy new clothes.

Most people looked at this catalogue in passing as you do with catalogues – well, some of us lingered on that dress. If we happened to think twice about the young girls in the catalogue, it was in noticing that they looked like they were happy. They were just standing there. Looking happy to be going to a party in their new clothes.

Someone else looked at this catalogue and thought these young girls were looking sexy. They thought that the clothes they were wearing made them look sexy. They said this fancy store was run by paedophiles because they had images of young girls looking sexy in their catalogue.

These people started a whole hoo-ha about how we were making children sexy before their time. They started looking at other things like girls dolls with giant heads and their sexy clothes. They said it was wrong. All of this sexualizing of young girls – because of happy looking girls in a catalogue.

But if you look at images of bored looking children and see something sexy, doesn’t that say more about you than about the children you’re looking at?

Anne-Frances Watson is a postgraduate student at Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia. She is working on the Developing Improved Sexual Health Education Strategies project for her studies.

Getting Real about Sexualization

Was there ever a more hypocritical government than the current UK one? On the one hand, the Department of Education told the chairman of the Mother’s Union, Reg Bailey, to produce a review of the commercialization and sexualization of childhood, ‘because so many parents feel their children live under pressure’. On the other hand organizations actually doing something against sexualization, for instance in the area of teenage pregnancy, have been subject to heavy budget cuts, or have simply been axed such as the Poppy Project, a London based housing project for victims of sexual trafficking.

Was there ever a dumber government than the current UK one? The review is built on three previous reviews (Byron, 2008; Buckingham et al. 2010; Papadopolous, 2010); not from the 1950s but from the last two years. Together these reviews have listed numerous very concrete and clearly written recommendations. But that was all done under Labour rule. Apparently, the current government considers sexualization and commercialization a party specific issue, and it needs Reg to produce particular Con-Libbish ‘robust and challenging recommendations’. I know a challenging recommendation, and a cheap one, that isn’t in the previous reports: ban the Page Three Girl of The Sun. If there is in-your-face sexualization, it is there.

Was there ever a government more blind than the current one? Do they really not want to see how children and teens resist and ignore sexualized and commercialized culture? It was in the UK wasn’t it, that a girl was banned from school for wearing a chastity ring vowing to abstain from sex until marriage? She is a devout Christian, but devout Muslim girls also refuse to submit to the pressures of sexualized culture. And one does not need a faith to resist sexualization and commercialization as the ‘straight edgers’ and ‘hard liners’ would know. Pony girls, hockey girls, Goths, queer girls, geek girls, they all have other priorities than sex and commerce.

Is there ever a government beyond redemption? No, and there is hope for this one if it cuts the surrogate action and ‘gets real’. Worried about childhood? Ask children themselves what their main concerns are, instead of having a vaguely defined group of ‘parents’, set their agenda. Family conflict and bullying could come out as their biggest problem, definitely before sexualization and commercialization. So focus the scarce government money on these areas even more than happens already, instead of moving reviews, reports and recommendations around in an endless circle of symbolic politics.

Liesbet van Zoonen is Professor of Communication and Media Studies at Loughborough University, UK. She is well known for her work on gender and media, especially for her book, Feminist Media Studies (1994). She has extensively analysed the articulation of politics with popular culture, most recently in the context of Islam debates. Her new book Media Panics: the public fear of entertainment, will come out in December of this year (with Sage).

What’s the evidence about young people’s sexual behaviour?

For sexualization activists, the negative consequences of sexualization – depression, eating disorders, precocious sexual activity and even sex work – are assumed to be self-evident, while scholarship that has complicated these facile claims are ignored. Research involving women that did not examine sexualization as a phenomenon at all have been used, after the fact, as ‘proof’ of sexualization (Egan and Hawkes 2009, 2007). The use of emotive terms like ‘objectification’ and ‘passive victims’ evokes oppressive patriarchal structures from the mid-twentieth century and encourages assumptions fed by unconscious fears. Legitimation is ensured by rhetoric and common sense replaces scholarly argument and empirical research.

But have we actually found ourselves in a world where tweens armed in their bralettes are ready and waiting to jump at the first chance for oral sex with an older man? Are they really just a hop, skip and a thong away from the sex industry? Are they watching, buying and listening their way to a future of depressive self-destructive behavior?

The insistent claims for the inevitable damage associated with sexualization centre round the distortion of young women’s ‘normal’ sexual development, where increasing promiscuity and declining self-worth and harm are presented as inevitable. Yet recent studies of young people’s sexual behavior in all three Anglophone countries, present evidence for responsible and thoughtful sexual behaviour in both young men and young women.

The National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior in the US (Herbenick et. al., 2010) found that in 62 % of boys and 40% of girls (aged 14-16) masturbation was the most common sexual practice. 9% of boys and 11% of girls had vaginal intercourse in the last twelve months while 79.1% of males and 58.1% of females used a condom in their last ten acts of heterosexual intercourse. In 2011 a Scottish study of 1800 14-16 year olds revealed that 32% had sexual intercourse at a median age of 14, and that 51% of these had used condoms. A 2008 study of 16-18 year students in Australia reveals a strikingly similar set of figures. Of 5000 young people interviewed, 78% had some form of sexual activity in the past year. Sexual intercourse contributed to 40% of this figure with 30% having 3 or more sexual partners. 50% of the sample used birth control pills and 69% used condoms for the last sexual intercourse (Smith et al., 2009).

It appears that 60 and 70% of young people in the age group under discussion are not engaged in intercourse. The most common method for seeking sexual pleasure is solo masturbation and, for partners, safe sex is a priority. That sexualization activists, who claim their priority is the protection of young girls, apparently ignore such evidence is inexplicable.

We suggest that this anomaly goes unremarked within the wider community because despite protestations of ‘what about the children’, academic and social commentators are deeply uncomfortable with the reality of the active sexual lives of young people, and (as we have illustrated elsewhere) this cultural discomfort has a long history (Egan and Hawkes, 2010).

Gail Hawkes teaches Sociology at the University of New England, Australia. She has been teaching and writing about sexuality since 1992 in the UK and in Australia. She is the author of A Sociology of Sex and Sexuality (1996, 2000, 2003), Sex and Pleasure in Western Culture (2004), (with John Scott) Perspectives in Human Sexuality (2005), and (with R. Danielle Egan) Theorizing the Sexual Child in Modernity (2010).

R. Danielle Egan is Professor of Gender and Sexuality Studies at St. Lawrence University, Canton, New York. Her publications include Dancing for Dollars and Paying for Love: Exotic Dancers and their Regular Customers (2006) and (with Gail Hawkes) Theorizing the Sexual Child in Modernity (2010).

Nine out of ten parents feel that their views on sexualisation are misrepresented. Probably.

There’s a useful test you can run on any campaign slogan: add ‘not’ to it. If it then turns into something that no sane person would be likely to support, you can be fairly sure that the original is equally nonsensical.

The sexualisation debate provides plenty of opportunities to try this out. The most recent series of Channel 4’s Sex Education Show, for instance, was entitled ‘Stop pimping our kids’. But who is making a case for ‘more sexual exploitation of minors now’?

Or take the mumsnet campaign to ‘Let Girls Be Girls’, where at least one can have fun imagining the opposition: mandatory state-funded sex change operations?

Being inane, however, does not mean ineffective: these slogans compel our assent, and indeed in the case of Mumsnet, emptiness and circularity are fundamental to reaching its audience. The campaign invites us to be part of a ‘we’ who know true girlhood, against a despicable ‘other’ who is at best ignorant and at worst bent on destroying it. Attempt to define what girls are or should do, however, and this cosy conspiracy will soon unravel: some associate girls with piano-playing and horse-riding, as if a privileged middle class existence is attainable and desired by all; feminists are unlikely to warm to the virtues of ‘pink tea parties and frilly dresses’ extolled by others; and those for whom ‘playing with dolls’ encapsulates innocuous girlishness presumably airbrush Bratz out of the picture.

Failing to define key terms, that is, makes a broad appeal more likely: it is a tactic helping anti-sexualisation campaigns persuade us that sexualisation is a ‘fact’ universally acknowledged by all persons of right mind and particularly by all who would lay claim to being a ‘good parent’.

Other tactics include referring to ‘widespread concern about sexualisation’, usually without evidence; although occasionally one encounters substantiating statistics, like a recent government press release announcing that ‘Almost nine out of 10 parents think that children are being forced to grow up too quickly’.

Is public opinion really so unanimous? These figures were generated by the Bailey Review of the Commercialisation and Sexualisation of Childhood, publicity for which explained that Reg Bailey ‘wants to hear from parents and carers about the pressures on their children to grow up too quickly’ via a survey. The first survey question listed ‘factors said to put pressure on children to grow up too quickly’, asked respondents to tick which ‘had the most influence on their own children’, and then to provide their own examples ‘of children being put under pressure to grow up too quickly’. In these circumstances, the real story is surely that ‘One in ten parents evades manipulation by survey’?

Another tactic is to embed a thoroughly partial view in what parades as simple description, thus disallowing any possible dissenting perspective. You may have read of the evils of pamper parties, which provide lessons in make up and fake champagne. How sinister – and how utterly unlike those carefree celebrations involving face painting and fizzy drinks.

The Sex Education Show adopted this approach, raging over the sale of studded pink hot pants (er…sparkly shorts?) for children. ‘We were shocked and so was the public’ declared presenter Anna Richardson, cutting to footage of ‘the people’ duly shaking their heads and tutting. But the makers had cued these responses by first asking them to interpret giant photos of single items before producing the petite actual merchandise, and by making it very clear what the ‘correct’ reaction would be.

I don’t want to single out this programme – one can’t stay cross for too long with a show otherwise so dedicated to filling our TV screens with close ups of wrinkled scrotums. Others have manufactured outrage in similarly artificial ways, as did the Sun newspaper’s campaign against a padded ‘paedo bikini’. But one has to ask why such devious tactics are necessary if the sexualisation case is as clear-cut and universally agreed as is claimed.

Put the questions differently and adults – like young people - readily admit the difficulties and uncertainties of these issues. Does an item of clothing on its own mean anything, or do you have to know something about who’s wearing it, when and where, and in combination with what (as when tiny shorts are worn with thick leggings and long tops)? What if all your kid’s friends have got them? Are girls’ shoes with heels acceptable if worn only for parties? Why are the cheaper chainstores more often targeted than, say, high-end ‘mummy-daughter’ boutiques selling scaled-down versions of womenswear for girls? Who has the right to declare a product ‘tasteless’ – is this just class prejudice in disguised form? Why is so much more attention paid to products for girls than for boys?

Go down this route and you’ll find yourself disappointingly short on ready-made solutions and policy-on-a-plate soundbites. But at least there’s a chance you’ll hear something other than what you think you already know.

Sara Bragg is a Research Fellow in Child and Youth Studies at the Open University, and co-author of Young People, Sex and the Media: the facts of life? (2004) and of Sexualised Goods Aimed at Children: a report to the Scottish Parliament Equal Opportunities Committee (2010)

The sexualisation of girls: beyond the moral panic

We’ve just come back from a Gender and Education conference where we organised a symposium on sexualisation and girls. We pulled together the session to respond to the moral panic aspects of the public debate with some empirical data with girls. Despite extensive debate there is still very little qualitative research on girls’ everyday sexual cultures and ‘sexualisation’. We have seen a tendency in some of the debates to either fix girls as either objectified passive victims of sexualisation or as agentic savvy navigators of sexualisation (usually with limited or no data with young people themselves). But we feel strongly that such binary positions do little to help us map the messy realities of how girls are living their sexualities in specific contexts. Our symposium looked at girls’ lives in different public, domestic and institutional spaces – e.g. social network sites, streets, elite and state schools. When young people’s experiences are made central to the analysis, we see how they can be positioned in multiple different ways simultaneously.

The day offered critical commentaries from educational scholars, paying attention to the wealth of assumptions, silences and myths around the seemingly ubiquitous sexualisation discourse. We wanted to ask: what are its effects on different groups of girls, in schools and beyond?

Claire Charles (Deakin University, Australia) put the sexualisation moral panic in context, taking a look at the proliferation of books by journalists and cultural commentators which bemoan the ‘sexualisation of girls’ from a popular feminist perspective. These books are targeted at concerned teachers, parents and health professionals. But at the same time, they form part of the same wider consumer culture that sells sexualisation, and often reinforce the neoliberal idea of the feminine, heroic, individual, can-do entrepreneur as the ideal for young womanhood – an ideal that ignores the realities of many girls’ lives.

Emma Renold (Cardiff University) and Jessica Ringrose (Institute of Education, University of London) talked about three ethnographic case studies of girls living in urban and rural working-class communities, and explored how young girls are navigating the contradictory expectations of young femininity. Teen girls were regulated by ‘new’ and ‘old’ sexual and gender regimes, which wanted them to be both ‘innocent’ and ‘sexy’ (often simultaneously). But at the same time, the girls reworked and resisted expectations – and they could take up ambivalent positions, and use signs and symbols of ‘sexualisation’ (like the Playboy bunny motif) in their own ways.

In contrast to this research on working-class girls, Naomi Holford (Cardiff University) spoke about the experience of white, middle-class teen girls, focussing the spotlight on girls whose identities are often seen as unproblematic and taken for granted. These girls had to walk a thin line, between being sexually desirable, competent and knowing, but not too knowing. The culture of ‘sexualisation’ had by no means created an environment where ‘anything goes’. Instead, many traditional conservative gendered double standards were still in evidence. Girls who didn’t follow peer group ‘rules’ – not showing enough moderation, having sex outside a relationship or not ‘looking after themselves’ properly – were often socially punished, and often judged each other (and were judged) in ways that maintained class prejudices. But within these constraints, they often found spaces to express their own sexualities.

Alexandra Allan (Exeter University) focussed on privileged groups of young people in elite single sex schooling, using ethnographic longitudinal data. This context is often seen as a ‘safe haven’ from sexualisation – girls’ schools have been marketed as a space to prolong the wholesomeness of childhood. Girls as well as teachers often bought into this idea of the ‘safe space’, and saw it as positive, but as Allan’s data showed, the reality was much more complicated. Teachers had to work hard to regulate the space, an often difficult task. As the girls got older, this regulation became much lighter (sometimes lighter than the girls themselves expected, and the young women negotiated their sexualities and ideas of risk in multiple ways in and outside the school – the single-sex, elite school wasn’t a singular and separate space.

Mindy Blaise (Hong Kong Institute of Education) returned to the heart of the ‘sexualisation of children’ moral panic, talking about her own experience as a researcher with 3-4 year olds. She looked at young children’s own understandings of sexuality and gender, through observations and talk about toys in early childhood settings. Her research was the subject of media coverage asking “Why can’t we let children be children?” – positioning the research as the problem, rather than looking at the ways it showed that children already held complex ideas about gender and sexuality. She called for a childhood sexuality research movement that went beyond the white, middle-class driven panic of contemporary sexualisation debates, paying attention to social and cultural differences, and looking at young children’s understandings and negotiations of ‘race’ and social class, together with gender and sexuality.

While she couldn’t make it to the conference Lucy Emmerson’s powerpoint addressed issues of sexualisation from the perspective of non-governmental organizations (Lucy is based at the Sex Education Forum). Her presentation would have drawn on the views of young people from online discussion forums and practitioner consultations to look at the role of sex and relationships education (SRE) in discussions about sexualisation. Her work explores adults’ lack of awareness about children’s understandings of sexuality and relationships, the mixed messages about young sexuality, and the problematic idea that talking or learning about sex and relationships ‘sexualises’ young people. She is thinking about how SRE might support ‘healthy sexual development’ as a positive alternative.

The symposium brought together research on very different groups of girls. But all the work shared a determination to take girls’ experiences and perspectives seriously, while remaining committed to exploring how those perspectives are shaped by cultural and social contexts. The public debate around ‘sexualisation’ is often based in anxiety and sometimes simplistic binaries of innocence versus sexuality. But the complexities of girls’ lives deserve to be given space.

We are carrying on these conversations at Cardiff University in June. So watch this space!

Naomi Holford is a PhD student in the School of Social Sciences, Cardiff University, UK. Her doctoral research focuses on gender and power in teenage heterosexual relationship cultures, especially in relation to middle-class teenagers’ experiences and identities.

Emma Renold is Reader in the School of Social Sciences, Cardiff University, UK. Her research focuses on the primary school as a key site for the production and reproduction of children’s sexual and gender relations. Her publications include Girls, Boys and Junior Sexualities: Exploring Children’s Gender and Sexual Relations in the Primary School (2005) and (with Carolyn Jackson and Carrie Paechter) Girls in Education 3-16: Continuing Concerns, New Agendas (2010).

Jessica Ringrose is Senior Lecturer in the Sociology of Gender and Education at the Institute of Education, University of London, UK. She is the author of Post-Feminist Education? Girls and the Sexual Politics of Schooling (forthcoming). With Meg Barker, Rosalind Gill and Emma Renold she organizes the ESRC Research Seminar Series, ‘Pornification? Complicating the debates about the sexualization of culture’.

Are we seeing the sexualization of children or the infantilization of adults?

Although few people seem to have a clear idea what ‘the sexualization of childhood’ actually means, there is a commonsense consensus that children today are ‘growing up too fast’. While lacking any clear definitions, compelling evidence or apparent causes, the sexualization issue is gaining international prominence because it brings together the many confusions and anxieties about intergenerational relationships, the boundaries between adulthood and childhood and the authority of parents. It contains a powerful dichotomy that lies at the heart of today’s parenting culture: parents are increasingly held responsible for all aspects of their child’s development but they are required to exercise this responsibility in a context that is pessimistic about the nature of contemporary childhood and that continually questions the capacity of parents to make the right choices on their children’s behalf.

We have been told for the past decade or more that the accumulated decisions parents (or more usually, mothers) make are the ultimate determinates of a child’s future life-chances. What women eat or drink during pregnancy, whether they breast or formula feed, what they cook, how often they speak, sing or read to their children have become things about which childcare ‘experts’, politicians, health professionals and celebrity chefs have strong opinions. Parents are caught in a maelstrom of competing yet dogmatic advice which casts them as the key risk-factor in their own children’s lives and which assigns the everyday, petty decisions of child-rearing an unprecedented significance not just for the individual child, but for the future of society. This culture of intensified yet expert-colonised parenting unsurprisingly makes parents feel relatively estranged from their own knowledge, values and instincts when it comes to raising their own children.

Parents are further disempowered by the strong cultural belief that past ways of raising children are irrelevant in a rapidly changing world. The idea that parents have little to offer children in the way of guidance and advice pops up continually in newspaper columns and everyday parental conversations. Books such as ‘Toxic Childhood’ by Sue Palmer, highly publicised reports such as the Unicef Innocenti Report Card on child well-being in rich countries and most importantly, government policy frameworks such as Every Parent Matters assert that children today are growing up in a dramatically different environment to that experienced by their parents whether through globalization, commercialization, technological advances or family breakdown. The message is that the experience and values of parents and the wider adult community have little relevance to the lives of 21st century children.

In the sexualization discussion, it is the overwhelming force of ‘the market’ that is blamed for prematurely sexualizing children whether by the sexual images used to sell goods to adults ‘infecting’ the world of children or by the direct marketing of ‘adult’ products to children. Parents are said to be ill-equipped to guide their children through a more visibly sexual culture without greater regulation or expert guidance and education. This ignores the fact that parents live within this same world, use the internet and presumably possess at least a modicum of experience of actual sexual relations. Initiatives like the Bailey review into sexualization reinforce the myth that ‘everything has changed’ and that normal family life is under siege from malign forces such as ‘the market’ or new technology. The idea that the world has been turned upside down, with children knowing more than their parents, is a disturbing myth that does not match the reality of most families but that nonetheless reflects the disorientation that many adults feel towards the future and appeals to our worst inclinations to give up and abdicate responsibility for raising the next generation as we see fit.

If we want childhood to be distinct from adulthood, we need to be clear about what it means to be an adult. Infantilizing parents by telling them that the world is a scary place from which they cannot protect their children without government reviews, censorship, regulation or even more intrusive expert advice is not a good place to start.

Jan Macvarish is a Sociologist at the University of Kent. She is convening a session on the sexualization debate at the forthcoming Centre for Parenting Culture Studies conference ‘Monitoring Parents: Science, evidence, experts and the new parenting culture’

It’s good to talk: Liberal parenting and the sexualization of children

Apparently we need to talk more to children. In BBC3’s reality TV series Sex with Mum and Dad, ‘upfront Dutch psychologist’ Maria Schopman encourages families to talk candidly about their sex lives with the aim of combating the risky sexual practices engendered by keeping sex secret. Channel 4’s Sex Education Show appealed to the same logic. Following complaints aimed at the show, Channel 4 released a statement claiming that ‘The series is aimed at families and we hope it will act as a starting point for a family discussion about the important issues raised’. On the website that accompanies the book So Sexy So Soon suggestions for ‘proactive parenting’ include limiting children’s exposure while also going beyond saying ‘no’ to children’s demands for sexualized products – these claims are managed through an invitation to talk more. Official reports include the advice that we should ‘encourage parents to talk to their children’, with suggestions that “parents can make sexualization visible by discussing media and other cultural messages with girls’. Given this trend, it is likely that the forthcoming report on the Commercialisation and Sexualisation of Childhood will also offer the advice that talking is a responsible parental practice.

In my research on the sexualization of culture, I was not seeking discussions on children’s sexuality – my focus being instead on how adult women made sense of a developing consumer culture of sexiness. I was surprised, therefore, at how much the women I spoke to wanted to talk about the sexualization of children. Moreover, women’s discussions of this sexualization oriented towards ways of speaking that allowed these women to present themselves as liberal free thinking parents, which I would argue offer new forms of regulation and uncertainty for both mothers and children.

One way the idea of the liberal parent came across in the interviews was through the assumption that openness equated to freedom and choice. For example, one woman said ‘I’m quite free with sex and provided that they’re making choices for themselves, and they’re being intelligent about contraception and sexually transmitted diseases, I think it’s fine’. What was evident in these discussions was that ‘freedom’ and ‘choice’ were available to the child; but these freedoms and these choices should also conform to privileged ideas surrounding the apparent dangers of teenage pregnancy, risky sexual practices and sexually transmitted diseases.

Forms of control offered by liberal parenting were also diametrically opposed to parents who did not discuss sexuality at all; ‘if you grew up, for example, in a household where sex is not talked about…then your first full on images of sex are what you would see online’. In as much as ‘repressive parents’ had no say in their children’s sexual education, they were deemed responsible for producing individuals who sought out ‘unhealthy’ and ‘unrealistic’ representations of sex. The repressed child was understood as necessarily looking to pornography to learn about sex (rather than, for example, formal sex education or indeed a sexual relationships with another person).

Finally, representing oneself as a liberal parent also meant that the women I spoke to self-monitored their own performance of motherhood. For mothers of young girls especially, women were torn between two contradictory ideas. On the one hand, women wanted to present themselves as liberal, yet on the other were aware of the wider moral panic and motherly concern as a response to the sexualization of girls. Combined with the forms of regulation discussed above, the liberal parent represented a new double standard for both mothers and young girls.

None of this is to suggest that talk is bad. Rather we need to construct new ways of talking about sexualization with children and young people that elide these regulatory discourses.

Adrienne Evans completed her PhD research at the University of Bath. Her research has explored women’s lived experience of negotiating sexiness in the twenty-first century. She has published work in the European Journal of Women’s Studies and Feminism and Psychology.

Sexuality education is stuck in a rut, and these ongoing sexualization debates are in part to blame.

Academics have been talking for years about how young people need a more comprehensive sexuality education. They’ve done a lot of research to back this up. As far back as 1978, Stevi Jackson spoke about sex education denying young people as sexual subjects. But, no matter how much research has been conducted we still aren’t telling young people enough about sex.

I’m becoming an academic. It sounds so boring. Luckily for me, my particular brand of academia includes talking openly in coffee shops about things like masturbation, sexuality, and pornography – in detail. My conversations draw embarrassed, humorous, and sometimes shocked looks from nearby coffee drinkers.

Growing up, I too was embarrassed and shocked about anything to do with sex. It wasn’t discussed in my house, and it certainly wasn’t discussed in my school. That is, unless you count the playground talk, which was all highly inaccurate and very confusing. Everything that I heard about sex pointed to it being wrong or dirty.

I blame these sexualization debates for much of the fact that sexuality education finds it so difficult to move forward. Refusing to talk to young people about sex for fear that they will immediately go out and start humping like rabbits at the mere mention of it seems more than a little bit counter-productive to me.

Young people are having sex. As much as we like to think back to the good old days when all sixteen year-olds were virginal and precious, we’re caught up in a mass delusion – those days never existed.

We need to start talking to young people about sex. We need to tell them that it’s natural, and healthy, and something they already know – it’s enjoyable. The media is too often blamed for telling them all of these things. Some of those smart academics have found that in fact, it’s their friends who are telling them quite a few things; it’s just been left to the media to give them the truth. If my childhood is anything to go by – their friends are telling them some very strange ways that they can fall pregnant.

Why has it been left to the media to deliver positive messages about sexuality? Instead of screaming for their heads, maybe we should thank them. Maybe we should say, how about we work together now, and give young people the information they so desperately want, and need?

Anne-Frances Watson is a postgraduate student at Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia. She is working on the Developing Improved Sexual Health Education Strategies project for her studies.

We need a wider analysis of inequality, not the surveillance of young people

The Government’s ‘Review of commercialisation and sexualisation of children‘ is being conducted in the context of wide ranging debates within academic, activist and popular media. It is a complex terrain for academics to research, with thorny questions of production, consumption and the relationship between media representations and behaviour at its heart.

The most recent Government review takes as its starting point a concern that children are being ‘sexualized’ at an early age. The aim of the review is ‘to address parents’ concerns that children are being pressured into growing up too quickly.’

Prime Minister David Cameron outlined his concern with this issue in the run up to the General Election last year in a comment piece in the Daily Mail. He set out his campaign against the “Products and marketing that can warp their minds and their bodies and harm their future. That can take away their innocence, which I know most parents would agree is so precious and worth defending”.

US academics Danielle Egan and Gail Hawkes contend that recent writing in this area tends to collapse concerns about corporation and media practice and consumption, ignoring historical and cultural variation. Rather than an examination of the diverse ways that children and young people access, read and understand media representations, the debate becomes condensed into concern about the contamination of ‘childhood innocence’ by sexual representations and products.

This is particularly evident in the way that young women and girls’ bodies and desires are represented in mainstream media debates about ‘the sexualization of children’. The images and stories that accompany news reporting in this area almost always focus on girls, drawing strict boundaries around the ‘appropriate’ or ‘good’ expression of feminine sexuality as innocent and passive, in contrast to the ‘bad’ or ‘dangerous’ expression of female sexuality as active and overt. Not only do such boundaries deny the existence of childhood sexuality and experimentation, they reinforce wider sexual norms on children, particularly girls, from a young age. ‘Good’ sexuality is typically therefore presented as heterosexual, monogamous and eventually productive of children. Signs of sexual desire outside of these boundaries are presented as negative and damaging to young people. Such boundaries are culturally specific and historical. James Kincaid (2004) has explored the investments that adults have in the production of childhood as non-sexual and non-erotic, and the foundations of such anxieties in the valorization and, paradoxically, the sexualization of purity and innocence in adult sexuality from the nineteenth century onwards.

The sharp policing of the boundary between ‘innocence’ and ‘danger’ in sexuality reflects and reinforces strong class anxiety. Imogen Tyler has analysed the rise of the abusive term ‘chav’ as a product of class disgust. Tyler explores the figure of the ‘chav mum’ as specifically vilified for her ‘excessive reproduction’ that does not fit the neoliberal narrative of participation in the workforce for greater economic growth. This anxiety is particularly reflected through language that signals disgust and marks out certain certain forms of consumption as respectable, and others as vulgar.

In Cameron’s comment piece above, as with some of the policy-led reviews on the subject, a link between the clothing young people are wearing and violence against them is made. Distaste for particular clothing is thus collapsed into a blame narrative. This perception that women and girls are responsible for sexual assaults perpetrated against them is concerning as a basis for policy. Such arguments lead towards policies that focus their attention on the surveillance and control of children, rather than on developing an understanding of the causes and effects of sexual violence.

In my view it is important that we explore the relationship between neoliberal capitalism and sexuality. The rise of individualism and narratives of empowerment through consumption form some of the conditions in which young people in the UK learn and start to experience their sexuality. As academics, policy-makers and activists we should seek to understand how young people negotiate these moments in all their complexity, from multiple social positions such as ethnicity, ‘race’, disability, class and gender.

However, the specific and repeated focus of analyses of ‘sexualization’ in isolation from a wider analysis of structural inequality is problematic. As David Buckingham and colleagues pointed out in the conclusion to their 2010 report on ‘sexualised goods’ aimed at children, the current framing of policy discussions about sexualization ‘may distract attention from other, more fundamental – and perhaps more intractable – social problems.’Social inequalities such as those that lead to sexual violence and poverty cannot be addressed through the lens of consumer choice and lobbying. Indeed, some of the greatest threats facing children in our society take shape in the reduction of council budgets that will lead to the closure of children’s centres and libraries, and in the job losses and benefits cuts that face parents in the coming years.

Laura Harvey is a doctoral student in the Department of Psychology at the Open University, UK, researching a thesis on the negotiation and representation of condom use in the UK. She is interested in the production of mediated sexual knowledges, identities and behaviours.

Queering the perspective: A call to recognize LGBT Youth in the sexualization of children debate

Throughout almost all of the public discussions regarding the sexualization of young people, the focus has overwhelmingly been heterosexual. If children are being robbed of their innocence, it is a heterosexual innocence that is at risk. When we talk of young girls being pressured by the media into dressing in ways that are deemed ‘inappropriate’, the fear of such inappropriateness is that it will be read through the lens of heterosexual masculinity. And when we express concerns regarding young men’s consumption of pornography, and the effects it might have on their attitudes towards sexual partners, the material in question is almost always presumed to be pornography made for heterosexual men and the imagined sexual partners are always posited as female.

Arguments regarding young people, the media and sexualization often neglect to recognize queer and non-normative sexual identities, practices or desires. This oversight is perhaps understandable (though not forgivable) given the fact that so much of the existing rhetoric posits those who need to be saved as ‘normal’ and ‘innocent’ – words that are almost wholly substitutable for ‘heterosexual’.

We need to queer this debate and in doing so we need to recognize the fact that, just as adults read and interpret the media in a plurality of ways depending on their beliefs, politics, desires, identities or backgrounds, so children and young people will inevitably understand and use the media they consume in multifarious ways.

Scholars ranging from Richard Dyer (1992) to Linda Williams (1992) to Brian McNair (1996) have argued for a more complex understanding of pornography, and of queer peoples’ consumption of pornographic material. Broadly speaking these researchers all identify the affirmative potential that such material can have for LGBT audiences. While acknowledging the fact that there may be issues of concern within queer pornographies that require further consideration(such as the representation of race, gender and uneven power relations), they identify the fact that, in a culture that privileges heterosexual relations and symbolically annihilates the desires and lives of queer people, queer pornography provides a space in which non-heterosexual bodies, practices and identities can be viewed and it validates such bodies, practices and identities. It says that male-male sexual desire is not only to be tolerated but can be ‘regular’. It suggests that lesbian sex that does not get ‘resolved’ or ‘straightened out’ by a male interloper is legitimate. It gives a voice to sexual desires that struggle to be heard in other media contexts and in doing so, it offers its audiences an opportunity to see their own desires reflected back in positive and affirming ways.

In spite of a raft of supportive legislation, the slowly increasing visibility of gay men (and to a much lesser extent lesbian, bi and trans people) in the media and the affordances of digital ICTs, queer youth still grow up in a society that presumes heterosexuality and privileges it as natural, normal and ‘healthy’. If proof were needed, one need only consider how many times one has heard a young boy or girl ‘come out’ as straight. Queer kids continue to experience a sense of isolation, atomization and loneliness growing up in such environments. Suicide figures for LGBT youth paint a grim picture that only serves to further underscore this assertion (Ryan et al. 2008).

The answer to such isolation does not lie solely with pornography. It cannot, because queer people are more than just desiring beings. However, the queering of the ‘sexualization and children’ discussion allows us to move beyond the binaries of ‘yes-no’ or ‘good-bad’ and recognize the different ways in which different young people might be using different types of pornography for different reasons.

Sharif Mowlabocus teaches Media Studies at the University of Sussex, UK. His research has included the ‘Count Me In Too’ project that contributes to progressive social change for local LGBT people in the Brighton and Hove area and work on safer sex education within gay male culture. He is the author of Gaydar Culture: Gay Men, Technology and Embodiment in the Digital Age (2010).

Nurturing Autonomy

While on a youth club field trip to the beach, a young man put his phone in front of my face. It was playing a porn film. I remember feeling disgusted and concerned. Knowing that this is one example among many, I can relate to the desire to ‘protect’ children and teenagers from the commercialisation of sex. At the same time, I ask myself, should I try to stop everything that makes me feel uncomfortable? Or can I allow myself to feel discomfort or even disgust without necessarily rushing to do something? If I support moves to ‘protect’ children, is it for their sake or mine? These are questions we might all be asking ourselves when we are called upon to save the children.

The language of protection can be used to justify control. Many of us are fed up with ‘health and safety’ regulations which are often more about protecting institutions from lawsuits than human health or safety. And a whole history of colonial profiteering, including the ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, has been justified with stories of protecting women. Neither war nor censorship does women or children any favours. Both do great harm, making women and children into helpless victims who always need ‘protecting’ by someone else who is big and strong. A big brother.

Government actions are often like this ̶ creating the appearance of well-being rather than actually nurturing it. To nurture well-being, in ourselves and each other, we might nurture autonomy. No one can do this for us. No law can make it happen. Autonomy means developing the skills to govern ourselves, to speak for ourselves, to listen to each other. As the award winning author Ursula K. Le Guin once wrote, “All of us have to learn how to invent our lives, make them up, imagine them. We need to be taught these skills; we need guides to show us how. If we don’t, our lives get made up for us by other people.” How might we all nurture imagination and empathy in ourselves so that we can be guides for each other?

I’m concerned that the problem isn’t just the commercialisation of sex, but the commercialisation of everything. The official economy depends on continual growth and prioritises profit over human dignity and the integrity of the ecosystem of which we are a part. Instead of simply trying to stop children from accessing corporate representations of sex, we might focus on nurturing a network of cooperative economies consistent with love, imagination and comfort with bodies. In this way, we can nurture autonomy in people of all ages and genders so that we are all able to care for ourselves and each other.

Instead of turning certain images of sex into forbidden fruit, making them all the more tempting, let’s acknowledge their existence and have open, gentle conversations about relationships, bodies and desires. Younger people are not dupes, not victims of culture. Like those of us who are older, they too have a mix of feelings, questions and stories about their experiences. To help each other face the challenges of our times ̶ including corporate uses of sex for profit ̶ we would do well to listen to each other. To really hear another, their voice must not be drowned out by our own thoughts and feelings. So before rushing to do something, I invite you to sit with thoughts, with feelings, to become comfortable with their presence. In my experience, this helps create space for the empathy and imagination needed to act with love.

Jamie Heckert taught sex education in Edinburgh secondary schools for 8 years. He is the author of several essays on ethics, relationships and desires and editor of two collections of writing on anarchism and sexuality.

Sex Shops: from the back streets to the high streets

Sex shops in the UK have traditionally been viewed as masculine consumption spaces, frequented in the margins of both the city and the clock – in decaying urban zones, hidden from view and visited under the cover of darkness. But in recent years, more and more new sex shops and ‘erotic boutiques’ such as Ann Summers and Coco de Mer are appearing on the high street, which are constructed as feminized sexual consumption spaces. Rather than being seen as seedy spaces in dangerous back streets, they are presented as light, fun, acceptable and safe, and above all, spaces for women to explore their sexualities.

The migration of sex shops to the high street has occurred because of changes in the sex shop licensing system. A proliferation of sex shops in Soho from the 1960s to 1970s, and a massive rise of sex shops in the rest of the UK, aroused concern over the ability to control them. This concern, alongside resistance from local communities, led to the creation of the Local Government (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1982, which meant that, by law, sex shops had to have a license to continue trading. However, a loophole in the licensing act, which states that a sex shop is only a sex shop if a ‘significant degree’ – usually considered to be 10% – of its stock is sex related (usually meaning pornography and sex toys). This meant that shops could continue to trade unlicensed if they reduced the proportion of sex articles they sold and increased the proportion of non-sex articles sold (usually in the form of lingerie).

The increase in the amount of lingerie sold encouraged a shift towards some shops being targeted towards the female consumer and led to the development of what I call the ‘feminized’ sex shop. This feminization is often marked by a more design led and fashion orientated style, emphasizing that they are light, playful, fun and sexy as opposed to seedy, dark and dangerous. Paradoxically then, the licensing system that was set in place to try and control the proliferation and location of sex shops, has actually helped put shops selling sex on the high streets. Yet while traditional sex shops are met with protests, feminized sex shops are often celebrated which is ironic as several Ann Summers shops are actually next to children’s toy shops.

The licensing system neglects to look at how sex shops for women market their products with advertising images of models with the ‘perfect’ female sexual form, which promotes the idea of women’s sexual fulfilment being equated with female beauty. Yet the opportunity for women to buy sex toys in a friendly, accessible, non judgemental retail environment is a step forward for female sexual liberation. It would seem that the transition of sex shops onto the high street requires greater critical attention, especially concerning how this affects female sexual empowerment.

Amber Martin is a PhD student at The University of Nottingham. Her research focuses on high street sex shops such as Anne Summers and Coco de Mer as ‘feminised’ spaces for sexual consumption.

Pornography: A filthy fruit

Throughout its history of some 200 years, the cultural status of pornography has been very much bound up with acts of policing and regulation. It can even be argued that the cultural status of porn has been dependent on the attraction of the forbidden fruit: As that which stands for the obscene, the filthy and the culturally worthless, porn has been cleared away and screened off from the public eye. At the same time, according to existing surveys, porn is popular in virtually all social groups and its popularity does not seem to increase in the course of filtering and regulation. Quite the contrary.

Concerns over pornography, and visual pornography in particular, tend to be based on its assumed power to impact its viewers directly. While porn does indeed regularly get under one’s skin, this viscerality may not be best understood as a corrupting force that people, and the young in particular are unable to resist. Porn is certainly visceral, as is horror, another popular genre. It does not, however, follow that porn holds some magical power to orient the drives and desires of those watching it. People do not simply repeat the acts shown on the screen in their everyday lives. The scenes and acts may resonate, titillate and interest but they are equally about distance and othering: for people also like to watch that which they would not themselves wish to do.

Since the Victorian era, the low cultural status of porn has been connected to its focus on the lower regions of the body that have equally been tied to notions of shame, secrecy and filth. It is perhaps even too easy to notice the Puritan underpinnings that seem to drive public debates on youth, sexuality and porn and turn them into moral panics. This is particularly the case in the United States but similar undertones are noticeable also elsewhere as debates on pornography become mapped onto particular notions of obscenity and filth, as well as particular understandings of proper or healthy sexuality.

In Nordic countries, the landscape looks somewhat different. Considered from a Nordic perspective that tends to highlight sexual health (as sexual autonomy and active sexuality) and sex education, the question is one of education that is capable of addressing pornography, of tackling the differences between porn as a media genre and sex as a set of physical practices, as well as acknowledging the variation between different pornographies. Porn is well known as sex education that precedes any institutional guidance on things sexual and since it focuses on sexual pleasure rather than the details of procreation or STDs that are popular in formal sex education, it enjoys a different kind of popularity. If simply screened off or forbidden, the attraction of porn is likely only to increase. And where there is interest, there will always be means of accessing pornography, independent of the filtering practices deployed.

Alan McKee has argued that the role of experts in matters pornographic has depended largely on them being unfamiliar with the topic, for it is considered a virtue not to know much about pornography. This is obviously not a sustainable stance to take in developing policies on pornography. At the same time, public memoranda and reports on the ‘pornification of culture’ far too often draw on anecdotal evidence and opinions rather than empirical research. They may even contradict empirical evidence, presenting opinions as facts. They tend not to listen to the young people concerned, thereby supporting the unhelpful view of adolescents as voiceless victims devoid of agency in terms of their own sexuality.

We need discussions on pornography and ethics, both sexual ethics and the ethics of porn production. We simply do not know enough about current production cultures of pornography to make any overarching arguments concerning them. Neither do we know enough about porn consumers and their experiences. We need to listen to these experiences in order to understand how pornography is both sensed and made sense of. Debates based simply on moralizing are of little help in understanding the changing role and position of pornography in media culture. They are guaranteed to miss the mark.

Susanna Paasonen is Professor of Digital Culture, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. She has written widely on the internet on on pornography. Her books include Pornification: Sex and Sexuality in Media Culture (2007), (with Marianne Liljeström) Working with Affect in Feminist Readings: Disturbing Differences (2010), and Carnal Resonance: Affect and Online Pornography (forthcoming).

Life before Internet porn: the golden years?

I’ve noticed a strange tendency in recent discussions about pornography and its influence on young people – an increasing romanticization of the world before the Internet, and of relationships between the sexes in those innocent days.

Take the ‘Reality and risk’ project for example, which aims to ‘promote critical thinking among young people about pornography and the messages it conveys about women, men and sex’. Their report states:

Young people are exposed to porn at unprecedented rates … They are seeing it more frequently, through more media, and what they are seeing is harder and more aggressive. Young people are living in an era of new sexual expectations, acceptance and practices. And, significantly, porn is normalising sex acts that most women in the real world don’t enjoy, and may find degrading, painful or violating. There is evidence that many young people are enacting porn scripts … The young women we interviewed talked about young men trying things they’d seen in porn, sometimes without even asking.

The language throughout this piece is of change. Young people are seeing porn at ‘unprecedented’ rates, ‘more frequently’, through ‘more media’. It’s ‘normalising’ sex acts – which clearly were not ‘normalised’ before. The effect of this change is that men are ‘trying things’ that women ‘may find degrading, painful or violating’, ‘sometimes without even asking’. The implication is clear – before Internet porn, men did not try to impose their sexual desires on women. If we could get rid of it then there would be no problems with consent or negotiation. There would be no issues with different sexual interests in couples. In the good old days before Internet porn, the argument runs, men treated women better. They took more interest in their sexual needs. They were more thoughtful, respectful lovers.

This worries me. Let me state this very simply: relationships between men and women have improved markedly since the 1970s. Young men these days have attitudes towards women that are better than their fathers had – and light years ahead of their grandfathers. We know this through empirical research – our survey for the book The Porn Report showed that young men had the best attitudes towards women of all the age groups. And if you doubt that it’s true, have a look at the writings of feminists before the advent of Internet pornography. Reviewing the 1970s, Gloria Steinem wrote at the end of the decade that:

Masculine dominance and female submission were still defined as “natural”; so much so that even violence towards women was accepted as a normal part of sexual life, Saturday night beatings and the idea that women “wanted” to be forced were all accepted to some degree … rape was finally redefined in the 1970s and understood as an act of violence … not a “natural” sexual need … [and] “battered women” was a phrase that uncovered a major kind of violence that had long been hidden. It helped us to reveal the fact that most violence in America takes place in our homes, not on the streets (1980: 23)

It’s true that things these days are far from perfect. Young women are still not encouraged to grasp sexual agency for themselves, whether they choose to use that agency to remain celibate, to have rampant sex with many people, or anything in between. And young men are still not encouraged to be reflective about what they want sexually and why. We still need, as Moira Carmody has argued, more extensive and systematic education in sexual ethics and consent for all young people. What we don’t need is to stick our heads in the sand and pretend that things were better in the good old days before Internet porn. Things weren’t better. Those weren’t the good old days. They were the bad old days, and relationships between young men and young women have improved immeasurably since then.

Alan McKee is Professor in Creative Industries at the Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia. He has written six books on media culture, and was the Chief Investigator of ‘Understanding pornography in Australia’, the first comprehensive examination of the production and consumption of pornography in Australia. This research was published (with Catharine Lumby and Kath Albury) in The Porn Report in 2008.

Making sense of the sexualization debates

I’ve been getting involved with events and projects about sexualization for some time now. I thought it was important for someone, like me, who writes about sexuality and who works with clients who are struggling with issues around sex, to be informed about what seems to be the big story about sex at the moment.

I’ve read lots of book chapters and papers, and watched many presentations, on the topic, and what is most striking to me are the complexities of the debate, and the feelings which run so high whenever we are talking about it. This is my attempt to give a simple overview of how I understand it, and to say where I’ve got to with it at this point.

The Simple Form of the Debate

The simple form of the debate, as it is played out on TV programmes, in policy documents, and in the huge number of popular books on the subject of sexualisation, goes something like this:

One side says that our society has become hyper-sexualised: wherever we go we are blasted with messages about sex. Boys are watching hardcore online porn from an early age and this is warping their sexualities and turning them into sexual predators. Girls are sexualised before they are out of toddlerhood with high-heeled baby shoes, playboy style mini T-shirts, and Bratz dolls. By the time they are teenagers they have bought the message that being sexy is all-important, putting them at risk of everything from eating disorders to STIs to sexual violence.

The other side of the popular debate emphasises choice and fun and power: we live in a time of equality, it says. People get to choose who they want to be. And if women want to go pole-dancing for leisure and feel empowered by dressing up sexy that is great. Lads magazines and sexy dancing on the X-Factor aren’t bad for women – they celebrate women – and anyone who disagrees needs to lighten up and get the joke.

The More Complex Form of the Debate

When the topic is debated in more academic circles, a somewhat more sophisticated version of these two sides tends to be put forward, which it would definitely be useful to get out there more widely:

The side that is concerned about sexualization says that all this emphasis on choice, fun and power makes it really difficult for people to resist messages about sexiness. To be a lad means always being up for it, and to be an empowered woman means choosing to pamper yourself so you look gorgeous and have all eyes on you. There’s no room for all the many, many men who feel anxious about sex, or all the women who don’t fit the very rigid standards of youth and beauty. And those that do fit live in fear of losing that.

The side that is more sceptical about sexualization points out that the whole thing seems like a moral panic: the kind of thing people get worked about every decade or so. Weren’t people panicking about mini-skirts and rock & roll in the same ways back in the 1950s and 60s? Talking with young people directly suggests that their sexual behaviour hasn’t changed that radically. They’re not all constantly sexting, watching porn, or trying every sexual practice that they see online. And lots of people find easier access to porn and other sexual information to be helpful in figuring out their own sexualities. People on this side of the debate ask questions like: Why are we so worried about sex instead of all the violent imagery that is out there unchallenged? Or whether all the concern that girls and women are in danger and need protecting from men reinforces divisions of gender, leading to more problems than it solves.

Where Do We Go From Here?

- Holding the tension: My main thought is that we need to move away from these either/or debates, not towards some resolution that is probably impossible, but more towards recognising the inevitable tensions and contradictions in the complex world we live in. We are massively shaped by the world around us, so current bombardment of sexual imagery is unlikely to leave any of us untouched, but we also all filter this through our own experiences and histories in unique ways so the same messages won’t have the same impact on everybody. We should be mindful of how these debates have played out in the past, and of who is included and excluded in them.

- Recognising what we bring to it: Emotions run high whenever these debates occur, and yet we all pretend that we don’t have a personal stake in it in order to make our points sound reasonable. It would be useful if we could acknowledge that being someone who watches porn, or a parent, or a person who does – or doesn’t – fit the current ideals of sexiness, influences how we come to these debates. And that the person we are arguing with will have similar, deeply personal, investments in it.

- Talking to people: A lot gets said on both sides of this debate based on assumptions, like looking at a music video and assuming it will make young people want to copy it, or assuming that because you feel able to resist some of these messages it will be just as easy for other people. We need to talk to people a lot more to find out how they are really being affected, and to help us remember that it is not the same for everyone.

Meg Barker is a Lecturer in Psychology at the Open University, UK. Her research focuses on social norms and rules around sexuality and gender and sexual communities, and especially on bisexuality, BDSM, and open non-monogamy. She practices as a sexual and relationship therapist and conducts workshops for therapists who are working with sexual or gender minority clients. Her publications include (with Darren Langdridge) Safe, Sane and Consensual: Contemporary Perspectives on Sadomasochism (2007), and (with Darren Langdridge) Understanding Non-monogamies (2009). She co-edits the journal Psychology and Sexuality with Darren Langdridge. Meg blogs here.

I’ve been following the current debates about sexualization with a lot of interest, both because I want to live in a sexually healthy world and because these sorts of discussions often have a direct impact on my work as a sex educator. And I’ve been sitting with the question of what a sex-positive response to the topic might be, especially after reading Renee Randazzo’s post on the Good Vibrations magazine and Peggy Orenstein’s post on mommyish.com.

My understanding of sex-positivity rests on the notion that the only relevant criteria for assessing a sexual act or practice is the pleasure, consent, and well-being of the people who choose it or who are affected by it. Of course, that’s easy to say and hard to practice, since it requires setting aside one’s internalized sex-negativity as well as one’s personal preferences and squicks. It’s also difficult to do because it’s a principle that must be applied in each unique situation, rather than an easy-to-implement rule.

So with that in mind, I want to take a look at the definition used by the APA Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls:

Sexualization occurs when

- a person’s value comes only from his or her sexual appeal or behavior, to the exclusion of other characteristics;

- a person is held to a standard that equates physical attractiveness (narrowly defined) with being sexy;

- a person is sexually objectified—that is, made into a thing for others’ sexual use, rather than seen as a person with the capacity for independent action and decision making; and/or

- sexuality is inappropriately imposed upon a person.

All four conditions need not be present; any one is an indication of sexualization. The fourth condition (the inappropriate imposition of sexuality) is especially relevant to children. Anyone (girls, boys, men, women) can be sexualized. But when children are imbued with adult sexuality, it is often imposed upon them rather than chosen by them. Self-motivated sexual exploration, on the other hand, is not sexualization by our definition, nor is age-appropriate exposure to information about sexuality.

From a sex-positive perspective, I can get behind much of this. When someone’s value is reduced to their sexual attractiveness, when sexy is defined in ways that exclude so many people, when people are treated as sexual objects (outside of the context of a specifically negotiated and consensual exchange), and when sex is imposed on others, we reinforce sex-negativity, sexual violence, and shame. And while I’d prefer if they’d phrased it as “any one can be an indication of sexualization, ” I do think it’s important to recognize the multiple directions that this can come from.

At the same time, given that sexual exploration is often motivated by both internal and external factors, I think it’s an oversimplification to make it seem as if it’s easy to determine that a particular person’s actions are self-motivated, especially if we don’t ask them. And we don’t actually know what “age-appropriate” means when talking about sex education, both because different children develop at different rates and because simply asking the question of what childhood sexual development looks like means risking being labeled a pedophile.

Unfortunately, in the quest to protect children from anything having to do with sex, people often create the circumstances that put them at more risk. In fact, so many of the ways that we respond to the challenges that we face around sexuality end up reinforcing the very problems that we’re trying to address that I can’t help but wonder if many of the anti-sexualization folks are doing it again. I’d really like to see more people critiquing and taking a stand against the narrow and limited views of sexuality that reinforce sexualization without resorting to shaming tactics that also reinforce sex-negativity. I’d like to see them advocating for a wider definition of what sexy is instead of attacking the one that dominates the discourse. I’d like to see them celebrating all bodies and advocating for sexuality education that teaches about consent, decision-making, and discovering about one’s authentic desires. I’d like to see them promote media literacy projects and help parents gain the language to talk with their children. I’d like to see them acknowledging that young people are active participants, even as their ability to make choices is shaped by their developmental stages. And I’d like to see more people advocating for both the freedom to be sexual in whatever way they choose AND the freedom from having any version of sexy imposed on them. It’s only freedom if you can say no as well as yes. Those are the kinds of things that help young people resist limited and limiting examples of how to be.

Other folks have pointed out the many flaws in the anti-sexualization movement’s rhetoric. It’s hard to get good information about this phenomenon when we each have a different set of experiences, and when we can’t really agree on what sex is (much less what “sexual” means). There’s also the issue of confirmation bias- how can a researcher code images as sexual or not without their individual sexuality influencing them? And then, there’s the question of whether they’re projecting a squick reaction instead of identifying something more general. I have to wonder how much of their concerns are because of discomfort with young people’s sexual expressions.

Yet, I still can’t discount everything that they say because I see some of the same patterns. I see how we’ve distilled “sex” into this one form that has no room for so many of the pleasure and joys that we can experience. I see how some young people try to make themselves fit a mold instead of celebrating their individualities. For that matter, I talk with plenty of adults who face the same struggles. Yes, I know lots of people also resist these representations, but the fact that they have to resist them worries me. These are hardly new dynamics. But as our culture has shifted into an attention economy, we’re inundated with more images that demand that we notice them. That changes the playing field in ways that we won’t understand for a while.

I don’t have any answers to many of these questions. All I know is that I’d like to see more people approaching with more sex-positivity and less shaming. I don’t think we’ll see any real answers until that happens.

Charlie Glickman been a sexuality educator since 1989. He is certified as a Sexuality Educator by the American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors and Therapists. He teaches classes for medical and mental health professionals, non-profit agency service providers, hotline volunteers, and many organization, communities and social groups. He also provide trainings and workshops about a wide range of sexual practices based both on clinical research and his extensive experience with thousands of individuals. His blog is here.

Blog Post

I was up watching “The Sex Education Show” last night, which has a campaign going on called ““. Now, in theory, this is something I agree with- do young girls really need padded bras if they aren’t developing breasts yet, should magazines like Front be at toddler height in WH Smith’s, and does anyone really need underwear that says “your pad or mine?” on the waistband? Of course when she says “kids” she mostly means girls, as people generally do. And really, is this a problem with “pimping kids”, or reflective of our issues with sexuality in general..?

The biggest problem of course, to me, was shown when the host showed little girls (at a pamper party, mind- makeup and temporary tattoos and nail polish were apparently ok) a selection of what she deemed “age inappropriate clothing”, and the girls loved them- unlike their mums. These girls were already buying into cultural ideas about female sexuality- being coquetteish, for example, or wearing eyeshadow and heels. But these aren’t cultural ideals that are pimped to children, though of course they pick up on them- they’re pimped to everyone. But that’s not addressed, of course.